A once-vacant Brewer building is now a startup hub that could be a model for Maine

When the ZF Lemforder auto parts plant in Brewer shut down in 2010, it took with it more than 100 jobs — a number that itself was down from its 1980s peak of about 400 employees.

But the cavernous, 126,000-square-foot building that housed the German company’s manufacturing operations has avoided the fate of many other Maine industrial properties that have seen their primary tenants close down or relocate and leave behind empty spaces.

Over the past decade, it’s become a hub for businesses that produce goods largely consumed outside of the Bangor region. They include a coffee roaster, a vodka distillery, a company that repurposes shipping containers and two companies that develop and manufacture composite materials.

Despite their differences, all five companies have one important thing in common: they were all started right here in Maine, by Mainers, and they employ more than 60 Mainers in total — a number that’s growing.

The transformation at a building that once housed a global auto parts manufacturer shows how local startups are gaining momentum in the Bangor region, gradually becoming something that could power the region’s future growth.

“There’s a chance to reimagine legacy industries and existing assets, like forest products, ocean products, composites, clean tech,” said Evan Richert, co-founder of Upstart Maine, a coalition of entrepreneur support programs in the Bangor region. “Nobody has really done that before here. It goes to the heart of whether or not eastern Maine can and will grow, and how it will grow. Will it be from outside? Or from within?”

A shift in approach

Throughout most of the 20th century, jobs in Maine were plentiful in industries such as logging, pulp and papermaking, and manufacturing. Then, as those jobs began to disappear, economic development organizations and municipal and state leaders scrambled to deal with the fallout.

The goal initially was to lure other large companies to the area to set up shop, just as General Electric had ended up in Bangor in the 1970s, and L.L. Bean’s customer service center did in 2005 before Wayfair’s center replaced it in 2016.

“For many decades, there was a very strong emphasis on developing real estate opportunities in order to attract enterprises from outside the state,” Richert said. “And that did work, in some cases. Bringing in big companies was, I would say, the strongest element of the regional approach to economic development.”

First, the Maine Venture Fund and Maine Technology Institute were created in the 1990s, investing state funds in promising and innovative Maine businesses.

Then, the University of Maine made big investments in research and development with an eye toward cultivating spin-off businesses. The Advanced Structures and Composites Center launched in 1996, and is today a world-renowned center for the research and development of composite materials. In 2006, the Foster Innovation Center opened, which helps students and staff at UMaine start and grow their own businesses.

And in 2001, the Target Technology Center opened in Orono, with the goal of becoming a hub for innovative new companies. In 2016, it was renamed the UpStart Center and became part of UpStart Maine, a nonprofit that serves as the umbrella for a number of regional entrepreneurial initiatives, including Top Gun and Scratchpad Accelerator, which coach entrepreneurs, and the Big Gig, a series of networking and pitching events that allow entrepreneurs to promote their businesses and secure funding.

It’s all aimed at building a culture of support for entrepreneurs so they can find resources to grow their businesses and the right talent, said Renee Kelly, UMaine’s assistant vice president for innovation and economic development.

“You have to create a critical mass of that,” she said. “I think we are on the cusp of that. There’s momentum now. But it takes a long time to build a culture.”

The Maine connection

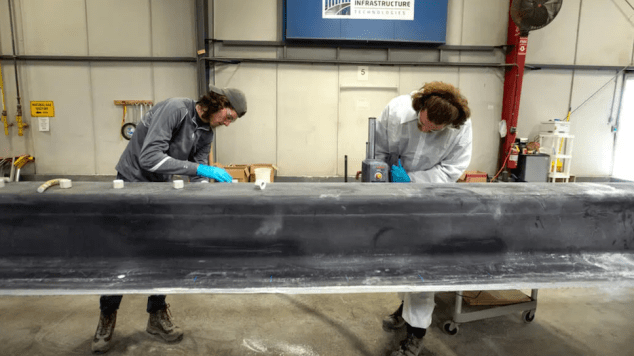

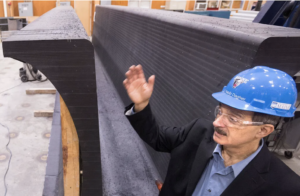

Two of the companies at the former Lemforder plant, AIT Bridges and Compotech, use composites technology to develop products for two different worlds: road infrastructure and the military. Both come directly out of UMaine’s Composites Center, which created the composites they use in their products.

Compotech, founded in 2011 by former Composites Center engineer and Vassalboro native Paul Melrose, uses composite materials developed at UMaine to create protective, secure structures for the U.S. military. Its first order of lightweight expeditionary shelters was shipped off to the government just last month, to be used in Army installations across the Middle East.

For Melrose, whose grandfather helped attract ZF Lemforder to Brewer decades ago when he was the city’s economic development director, bringing Compotech to Brewer was not just about finding a place to house his business.

“I worked to get AIT into this building so we could build what has become a composites hub,” Melrose said. “One of my goals for this was always to bring back manufacturing to the area.”

AIT Bridges was founded in 2009, after it became apparent that the composite materials developed at the Composites Center had potential in the infrastructure world. After a period of securing federal approval to use those materials for bridges and other structures, AIT’s products now compete against materials such as steel and concrete when governments put infrastructure projects out to bid.

AIT’s work is most easily visible in the Bangor area at the Grist Mill Bridge, which carries Route 1A over the Souadabscook Stream in Hampden and was installed last year. It is the first bridge in the country to use fiber-reinforced polymer tub-girders called GBeams, developed at the Composites Center and licensed by AIT. The substance is lighter and cheaper than concrete or steel, and will last more than 100 years with little to no maintenance required.

The next bridges the company will install will also use GBeams — a second bridge in Hampden as well as structures in Rhode Island and Florida.

“It’s a game changer,” said Brit Svoboda, AIT’s CEO. “And we do it here in Maine. We’re hiring Maine people. And it’s an incredible partnership between us and the University of Maine.”

AIT Bridges presently employs 20 full- and part-time employees, and expects that number to grow by 25 to 50 in the next two years. Similarly, Compotech currently employs 16 full-time employees and is regularly hiring new people. That puts the five companies in the former ZF Lemforder building on track to employ around 100 people in the coming years, replacing most of the jobs that disappeared when the auto parts manufacturer left Brewer.

In addition to Compotech and AIT, Twenty2 Vodka has distilled its several varieties of vodka in the building since moving there from Houlton in 2013, Coffee Hound Coffee Company has roasted coffee there since 2019 and was named the most exciting Bangor-region startup last year by UpStart, and SnapSpace Solutions has converted old shipping containers in the space since 2011.

Back to the roots

The Brewer building is just one of several startup hubs in the area. The Bangor Innovation Center has been a longtime incubator for small businesses, since it was founded in the early 1990s in a building near Bangor International Airport that was formerly part of Dow Air Force Base.

“This is the most activity I have ever seen in this space, by a longshot,” said Steve Bolduc, who has managed the center for more than 30 years. “There can be up to 50 people working here on some days. That’s a major increase.”

Among those businesses are Cerahelix, a company that has its roots at the University of Maine and manufactures specialized water filtration systems. While Cerahelix, which moved there in 2020 after previously being located at the UpStart Center in Orono, is developing innovative new technology, its neighbor Higgins Fabrication is reimagining another legacy Maine industry — wooden furniture making — for the 21st century.

Keven Higgins started his company in his Holden home’s garage in 2014. A woodworker since he was a child, he made the jump that year into doing it professionally, and quickly found a niche in making high-end dining, conference, and coffee tables and desks, using hardwoods such as walnut, maple and birch, with colorful resin poured into cavities in the wood.

When the pandemic struck, he, like any small business owner, was worried about what might happen. To his surprise, around May 2020, his business exploded, as people sat at home and decided they wanted to spruce up their houses. Higgins has hired three more employees this year, bringing his staff to seven, and hopes to take over another space at the Innovation Center.

“This business, as it exists now, could not have existed 20 years ago, and that’s entirely because of the internet,” Higgins said. “People find us because of that. We operate out of Bangor, Maine, and we can reach markets that otherwise would be impossible without the online marketplace.”

Looking toward the future

Those working with small businesses in the area agree that an eastern Maine economy driven by homegrown startups is still at least a few years away, with the region’s employment picture still dominated by health care and services.

“I think we have to work on both ends of it — attracting people from outside, while nurturing what is here,” said Jason Harkins, associate dean of UMaine’s business school and managing director of UpStart’s Scratchpad Accelerator. “But as for startups, it’s almost never something where it explodes after just a few years. It’s a long gestation period. It can take 10 years or more for a business to fully mature.”

That said, the startup economy in the Bangor region is better positioned for growth now than it has likely ever been, Harkins said.

“People are so much better connected now than they were even just 10 years ago,” he said. “The kind of rural innovation that’s happening now is because people are more plugged into the resources that are available to them, and coordinate with each other and with the organizations that are there to help them.”

Kelly said the pandemic might also have opened up an opportunity for Maine.

“I think people are much more comfortable now with interacting digitally, instead of in person,” Kelly said. “There’s been a lot of research on how investors only invest in places nearby them, but I think some of that is starting to melt away because of the pandemic. And the same goes for talented people relocating to Maine, because they can work remotely. It’s too soon to say if that will pan out, but that’s a door that wasn’t open before.”

Where will businesses such as AIT Bridges, Higgins Fabrication or Coffee Hound be in five years? Time will tell, but Richert believes it’s smart to bet on businesses like them.

“It’s not a revolution, per se,” he said. “It’s an evolution. It’s a long process. It’s playing the long game. But if I were to bet, I’d bet on startups.”

Article by

A once-vacant Brewer building is now a startup hub that could be a model for Maine